Exploring Race and Citizenship in Early Nineteenth-Century New York

Prithi Kanakamedala, Bronx Community College (CUNY)

Keywords: Self-determination, citizenship, community

Course: African American History (Survey)

In spring 2017, I taught African American History which is offered as an elective by the history department at Bronx Community College (BCC) of the City University of New York (CUNY). Students usually choose one of two main courses that has multiple sections (HIS 10 The Modern World or Global History Survey and HIS 20 The American Nation or U.S. History Survey) to fulfill their degree requirements. If students register for an elective such as HIS 37 African American History, it is generally because they have a personal and/or scholarly interest in the course. Given my research interests, and after a significant curriculum overhaul, I wanted to incorporate the following into the class:

- Draw upon new scholarship in African American studies with an emphasis on transnational approaches,

- Develop students’ ability to examine and evaluate primary sources, and draw substantiated conclusions from their analysis,

- Complicate ideas of race, especially in early nineteenth-century New York,

- Use my own research in my teaching,

- And deepen students’ historical knowledge of community building, self-determination, and instances of political solidarity between communities of color.

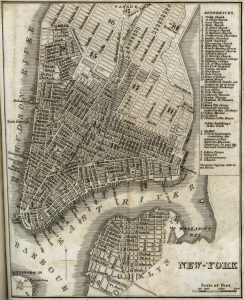

My current research looks at the DeGrasse family – New Yorkers of African and South Asian descent – who lived in Manhattan’s Five Points, or modern-day Chinatown. George DeGrasse was born Azar LeGuen in Calcutta, India, and married Maria Van Surlay, who was of African, Moroccan, and Dutch descent. George, Maria, and their neighbors built institutions (churches, mutual aid societies, and schools) intended to create strong communities of color and combat white supremacy.

Students were placed in groups and completed the following scaffolded assignment over two class sessions (1 hour 15 mins each).

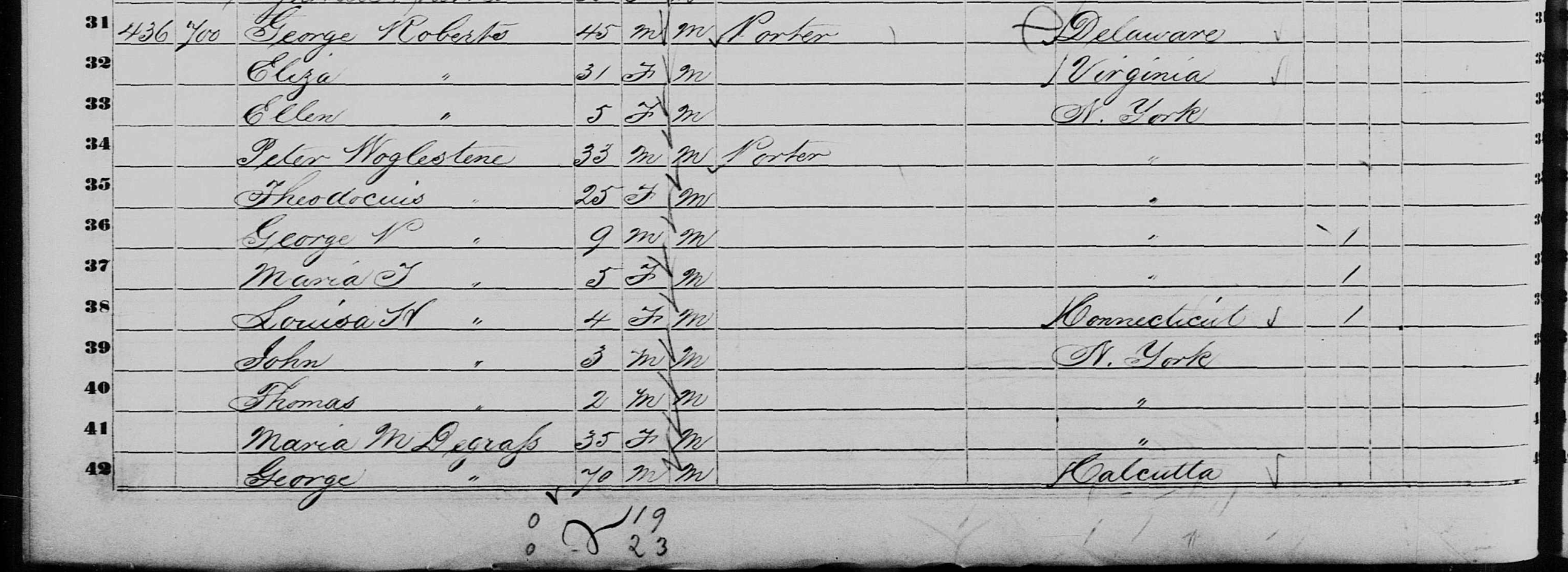

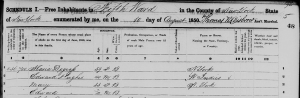

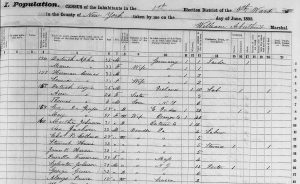

Students were asked to write down answers to a series of highly structured questions, e.g., what “color” is George listed as? Where were people in dwelling 700 born? And finally they were asked to draw conclusions about the diasporic nature of New York’s early free Black communities.

Again, using a series of structured questions and their analysis from the federal census, students looked at how George and Maria’s “color” had changed, listed the number of naturalized voters of color, and considered the reliability of census material for historians, and the type of work open to people of color.

Finally, students looked at Primary Source 3, an excerpt (pp. 311-317) from William C. Nell’s Colored Patriots of the American Revolution (1855).

By the end of the two sessions, students led a discussion on the diversity of New York’s neighborhoods in the early nineteenth century, drawing parallels between communities now and then. They also discussed how free people of color had to find ways to establish their dignity and humanity given the limited labor market at the time. Finally, they wrote a short paper on the contentiousness of citizenship until the 14th Amendment (1868), both for immigrants of color and those born on U.S. soil. It was a good place, early in the semester, for students to start thinking about historical communities of color being as complex as their own – especially in this early example of Asian American and African American solidarity – and to think beyond the discipline of history as the memorization of places, names, and dates, but rather deep critical thinking around issues and themes that still impact their lived experiences today. Like the borough itself, BCC has a steadily increasing population of people of Pakistani and Bangladeshi descent, and my hope is that my students who mostly identify as Latin@ and/or Black can use the past to understand their present.